| ||

| Wrong Again v. Un chien andalou |

Consider it sacrelidge, but this film fan will always prefer the warmer,more human side to anarchistic humor in Leo McCarey than the cynical, surreal (albeit masterful) work of Luis Buñuel. Maybe it's because I subscribe to a Sullivan's Travels school of personable (if naïve) optimism in which comedy unites rather than divides. Maybe it is because the rust seems to gather more quickly on work with a cutting social message. Maybe it's because, at the end of the day, Leo McCarey, dying of emphysema, could look back on a career in which he understood people, as Jean Renoir said, "better than any other Hollywood director", while Luis Buñuel wrote, "I can only wait for the final amnesia, the one that can erase an entire life". Maybe it is naïve, but the history of film is one that records ourselves in a very distinct time. To at once be within and transcend this time it no easy feat, and one that the best slapstick does maybe better than any genre. Thanks to the persistence of a number of European film historians, the art of Charley Bowers has now been rescued from public amnesia.

The details of Bowers's life make his two-reeler Now You Tell One seem autobiographical. In the film, a group called The Liars Club compete to impress with the most outlandish stories (the least of which marches elephants up Capitol Hill, the greatest involving a magic potion that will grow even inanimate objects through a grafting process). In his real life, he was purportedly kidnapped by the circus at age six, trained as a professional tightrope walker, and eventually worked in bronco busting and animation before getting into film. Even the details surrounding his co-director, Harold L. Muller are sketchy at best, leading historians to question his existence.

As a clown, Bowers has the stature and posture of a Buster Keaton but understands he can't compete in overall physicality and choreography of gags. Bowers's imagination is just as anarchistic on a large scale and, if not embodied in his physical presence, is substituted in his animation and, for lack of a better word, magic. Not quite deadpan, Bowers carries about him the same unaffectedness of the courtier like Keaton, and the gags work because this wide-eyed naïveté (tying him to probable influence Harry Langdon) allows the machinery to take the limelight. Bowers's machines never quite work, but they don't consume us as in Modern Times, and the inventor is never exasperated with how little he gets out of how hard he works (in essence, Harold Lloyd's schtick). Bowers's legacy extends the magic of Georges Méliès to slapstick, Rube Goldbergian levels, and sets the bar of fluid, anthropomorphic, stop-motion animation so high that no one--not the Brothers Quay, not Wladyslaw Starewicz, not Aardman Animations-- has neared.

|

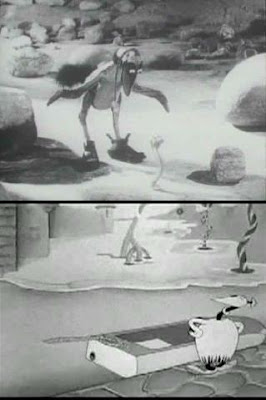

| Egged On (1926) |

To call Bowers's work anti-Modernist somewhat misses the point. Bowers plays an inventor in many of his shorts--an inventor named Charley Bowers in some of them. And as you would expect in slapstick, the machines often go wrong. In Egged On, in an attempt to make an unbreakable egg, Charley instead invents an egg that takes on the nature of what broods it. Sure, the contraption eventually creates what destroys it, but the machine isn't the enemy. Compare this to He Done His Best (a better-realized version of his earlier, animated The Extra-Quick Lunch) in which it is the violence of the human element--the union--that is responsible for (just as in Egged On) blowing up the room. It is the machine that offers a solution. Ultimately, the films of Charley Bowers poke fun at Modernism without being critical of it. While the joke is often non sequitur, Bowers hardly prescribes to the surrealist philosophy. To our benefit, these two-reelers follow narrative structures and are absurd without the weight of philosophy. Hardly fundamentalist, the surrealism in Bowers's gonzo imagination suggest that anything is possible. Though holding to some traditionalist ideas (marriage and earning a living), Bowers's heroes are always more a product of their time than holding to established dogma.

|

| A Wild Roomer (1927) |

Often, when Bowers resorts to his clown to be sole source of humor, there is a mean streak that suggests his work was more concerned with populist success than social cohesion or devotion. Perhaps this is why he was a such a success in Europe which, to this day, celebrates a heavy-anarchistic-over-common-

|

| It's A Bird (1930) v. Porky In Wackyland (1938) |

The anarchistic humor of Bowers isn't only seen in Clampett and Chuck Jones, it is evident in much of the best work of Dave and Max Fleischer in not only spirit (Bimbo's Initiation) but structure (Betty Boop's Crazy Inventions). The Fleischer's return the favor in bringing on Charley Bower for 1940's Wild Oysters. Like Nothing Doing was to his earlier slapstick work, Wild Oysters seems to be an earlier effort which lacks the ingenuity and fluidity of his earlier animated efforts. The oyster-out-of-his-shell gag was better used in He Done His Best, and is recycled here in what essentially boils down to animals doing cruel things to one another. Nevertheless, it is a welcome convention that inspired many Looney Tunes cat and mouse shorts in the 1940s. Even the one-off gags like the automated dancing shoes in Fatal Footsteps shows the influence an all-but-forgotten film can have decades later ("The Jetsons", "The Simpsons").

What stands out most in the work of Charley Bowers is his technical wizardry. Not to belittle the work of the Looney Tunes animators, Hannah-Barbera or Matt Groening and co., but the world was their 2D oyster. Bowers level of craft is remarkable in any time frame. What he was able to accomplish for stop-motion 3D animation is difficult to imagine. That he did it in the 1920s is unfathomable. And the man was no slouch when it came to straight clownin' either. The man is a treasure whose work is remarkably unheralded considering his average output trumps the average Charley Chase, Mack Swain or Harry Langdon picture. Given the time, what remains of his work will find its audience much like Leo McCarey's masterpiece Make Way For Tomorrow has after remaining in the dark for over half a century. We can only hope.

A.W.O.L. (1918) -- ** /four stars

The Extra-Quick Lunch (1918) -- **½ /four stars

Egged On (1926) -- ****/four stars

He Done His Best (1926) -- ***½ /four stars

Fatal Footsteps (1926) -- ***/four stars

Now You Tell One (1926) -- ****/four stars

Many A Slip (1927) -- ***½ /four stars

Nothing Doing (1927) -- **½ /four stars

A Wild Roomer (1927) -- ***½ /four stars

There It Is (1928) -- ****/four stars

Say Ah-h! (1928) (fragment) -- ***½ /four stars

It's A Bird (1930) -- ****/four stars

Believe It Or Don't (1935) -- ** /four stars

Pete-Roleum and His Cousins (1939) -- *½ /four stars

A Sleepless Night (1940) -- **½ /four stars

Wild Oysters (1941) -- **½ /four stars

No comments:

Post a Comment